Emission spectrum

The emission spectrum of a chemical element or chemical compound is the spectrum of frequencies of electromagnetic radiation emitted by the element's atoms or the compound's molecules when they are returned to a lower energy state.

Each element's emission spectrum is unique. Therefore, spectroscopy can be used to identify the elements in matter of unknown composition. Similarly, the emission spectra of molecules can be used in chemical analysis of substances.

Contents |

Emission (light)

In physics, emission is the process by which a higher energy quantum mechanical state of a particle becomes converted to a lower one through the emission of a photon, resulting in the production of light. The frequency of light emitted is a function of the energy of the transition. Since energy must be conserved, the energy difference between the two states equals the energy carried off by the photon. The energy states of the transitions can lead to emissions over a very large range of frequencies. For example, visible light is emitted by the coupling of electronic states in atoms and molecules (then the phenomenon is called fluorescence or phosphorescence). On the other hand, nuclear shell transitions can emit high energy gamma rays, while nuclear spin transitions emit low energy radio waves.

The emittance of an object quantifies how much light is emitted by it. This may be related to other properties of the object through the Stefan–Boltzmann law. For most substances, the amount of emission varies with the temperature and the spectroscopic composition of the object, leading to the appearance of color temperature and emission lines. Precise measurements at many wavelengths allow the identification of a substance via emission spectroscopy.

Emission of radiation is typically described using semi-classical quantum mechanics: the particle's energy levels and spacings are determined from quantum mechanics, and light is treated as an oscillating electric field that can drive a transition if it is in resonance with the system's natural frequency. The quantum mechanics problem is treated using time-dependent perturbation theory and leads to the general result known as Fermi's golden rule. The description has been superseded by quantum electrodynamics, although the semi-classical version continues to be more useful in most cases.

Origins

When the electrons in the atom are excited, for example by being heated, the additional energy pushes the electrons to higher energy orbitals. When the electrons fall back down and leave the excited state, energy is re-emitted in the form of a photon. The wavelength (or equivalently, frequency) of the photon is determined by the difference in energy between the two states. These emitted photons form the element's emission spectrum.

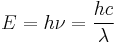

The fact that only certain colors appear in an element's atomic emission spectrum means that only certain frequencies of light are emitted. Each of these frequencies are related to energy by the formula:

where E is the energy of the photon, ν is its frequency, and h is Planck's constant. This concludes that only photons having certain energies are emitted by the atom. The principle of the atomic emission spectrum explains the varied colors in neon signs, as well as chemical flame test results mentioned above.

The frequencies of light that an atom can emit are dependent on states the electrons can be in. When excited, an electron moves to a higher energy level/orbital. When the electron falls back to its ground level the light is emitted.

Radiation from molecules

As well as the electronic transitions discussed above, the energy of a molecule can also change via rotational, vibrational, and vibronic (combined vibrational and electronic) transitions. These energy transitions often lead to closely spaced groups of many different spectral lines, known as spectral bands. Unresolved band spectra may appear as a spectral continuum.

Molecular emission is the mechanism behind the sulfur lamp and the deuterium arc lamp.

Emission spectroscopy

Light consists of electromagnetic radiation of different wavelengths. Therefore, when the elements or their compounds are heated either on a flame or by an electric arc they emit energy in form of light. Analysis of this light, with the help of a spectroscope gives us a discontinuous spectrum. A spectroscope or a spectrometer is an instrument which is used for separating the components of light, which have different wavelengths. The spectrum appears in a series of lines called the line spectrum. This line spectrum is also called the Atomic Spectrum because it originates in the element. Each element has a different atomic spectrum. The production of line spectra by the atoms of an element indicate that an atom can radiate only a certain amount of energy. This leads to the conclusion that electrons cannot have just any amount of energy but only a certain amount of energy.

The emission spectrum can be used to determine the composition of a material, since it is different for each element of the periodic table. One example is astronomical spectroscopy: identifying the composition of stars by analysing the received light. The emission spectrum characteristics of some elements are plainly visible to the naked eye when these elements are heated. For example, when platinum wire is dipped into a strontium nitrate solution and then inserted into a flame, the strontium atoms emit a red color. Similarly, when copper is inserted into a flame, the flame becomes green. These definite characteristics allow elements to be identified by their atomic emission spectrum. Not all lights emitted by the spectrum are viewable to the naked eye, it also includes ultra violet rays and infra red lighting, an emission is formed when an excited gas is viewed directly through a spectroscope.

Emission spectroscopy is a spectroscopic technique which examines the wavelengths of photons emitted by atoms or molecules during their transition from an excited state to a lower energy state. Each element emits a characteristic set of discrete wavelengths according to its electronic structure, by observing these wavelengths the elemental composition of the sample can be determined. Emission spectroscopy developed in the late 19th century and efforts in theoretical explanation of atomic emission spectra eventually led to quantum mechanics.

There are many ways in which atoms can be brought to an excited state. Interaction with electromagnetic radiation is used in fluorescence spectroscopy, protons or other heavier particles in Particle-Induced X-ray Emission and electrons or X-ray photons in Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy or X-ray fluorescence. The simplest method is to heat the sample to a high temperature, after which the excitations are produced by collisions between the sample atoms. This method is used in flame emission spectroscopy, and it was also the method used by Anders Jonas Ångström when he discovered the phenomenon of discrete emission lines in 1850s.

Although the emission lines are caused by a transition between quantized energy states and may at first look very sharp, they do have a finite width, i.e. they are composed of more than one wavelength of light. This spectral line broadening has many different causes.

Emission spectroscopy is often referred to as optical emission spectroscopy, due to the light nature of what is being emitted.

History

Emission lines from hot gases were first discovered by Ångström, and the technique was further developed by David Alter, Gustav Kirchhoff and Robert Bunsen.

See spectrum analysis for details.

Experimental technique in flame emission spectroscopy

The solution containing the relevant substance to be analysed is drawn into the burner and dispersed into the flame as a fine spray. The solvent evaporates first, leaving finely divided solid particles which move to the hottest region of the flame where gaseous atoms and ions are produced. Here electrons are excited as described above. It is common for a monochromator to be used to allow for easy detection.

On a simple level, flame emission spectroscopy can be observed using just a Flame and samples of metal salts. This method of Qualitative analysis is called a Flame test. For example, Sodium salts placed in the flame will glow yellow from Sodium ions, while Strontium (used in road flares) ions color it red. Copper wire will create a blue colored flame, however in the presence of Chloride gives green (molecular contribution by CuCl).

Emission coefficient

Emission coefficient is a coefficient in the power output per unit time of an electromagnetic source, a calculated value in physics. The emission coefficient of a gas varies with the wavelength of the light. It has units of m s^(-3) sr^(-1).[1] It is also used as a measure of environmental emissions (by mass) per MWh of electricity generated, see: Emission factor.

Scattering of light

In Thomson scattering a charged particle emits radiation under incident light. The particle may be an ordinary atomic electron, so emission coefficients have practical applications.

If X dV dΩ dλ is the energy scattered by a volume element dV into solid angle dΩ between wavelengths λ and λ+dλ per unit time then the Emission coefficient is X.

The values of X in Thomson scattering can be predicted from incident flux, the density of the charged particles and their Thomson differential cross section (area/solid angle).

Spontaneous Emission

A warm body emitting photons has a monochromatic emission coefficient relating to its temperature and total power radiation. This is sometimes called the second "Einstein coefficient", and can be deduced from quantum mechanical theory.

Energy spectrum

An energy spectrum is a distribution energy among a large assemblage of particles. It is a statistical representation of the wave energy as a function of the wave frequency, and an empirical estimator of the spectral function. For any given value of energy, it determines how many of the particles have that much energy.

The particles may be atoms, photons or a flux of elementary particles.

The Schrödinger equation and a set of boundary conditions form an eigenvalue problem. A possible value (E) is called an eigenenergy. A non-zero solution of the wave function is called an eigenenergy state, or simply an eigenstate. The set of eigenvalues {Ej} is called the energy spectrum of the particle.

The electromagnetic spectrum can also be represented as the distribution of electromagnetic radiation according to energy. The relationship among the wavelength (usually denoted by Greek " "), the frequency (usually denoted by Greek "

"), the frequency (usually denoted by Greek " "), and the energy E are:

"), and the energy E are:

where c is the speed of light and h is Planck's Constant.

An example of an energy spectrum in the physical domain is ocean waves breaking on the shore. For any given interval of time it can be observed that some of the waves are larger than others. Plotting the number of waves against the amplitude (height) for the interval will yield the energy spectrum of the set.[2]

Optical Spectroscopy and Astrophysics Application

Energy spectra are often used in astrophysical spectroscopy.

The quantity plotted, energy units, is the wavelength times the energy per unit wavelength and thus accurately represents the amount of energy at any wavelength. The energy per unit wavelength and the energy per unit frequency peak at significantly different wavelengths due the reciprocal relation between frequency and wavelength. Using energy units avoids this problem, since (wavelength * flux per unit wavelength) = (frequency * flux per unit frequency).

Some modern spectrophotometers, such as the Perkin Elmer 950, include an energy scan option. This is additionally useful in cases where a reference cell is not practical or when absorbance / transmittance is off-scale.[2][3]

See also

- The Diode equation includes the emission coefficient

- Plasma physics.

- An emission coefficient is also given for ballistic secondary electron emission.

- Luminous coefficient

References

External links

- NIST Physical Reference Data—Atomic Spectroscopy Data

- Color Simulation of Element Emission Spectrum Based on NIST data

- Hydrogen emission spectrum

- Emissions Spectrum Java Applet

- Astrophysics lecture slides on the emission coefficient from University of Chicago.